Keyak: a candidate for the authenticated encryption standard

17 February 2020New authentication cipher

Keyak is an authenticated crypto system that is based on the Keccak sponge primitive. It is a candidate for the authenticated encryption standard in NIST’s Caesar competition. For those not familiar, Keccak is the recent new standard for a hashing algorithm, SHA-3. The sponge primitive is a neat construction. By itself, it is a secure hashing primitive, but can easily be extended to provide encryption, pseudo random number generation, and authentication primitives.

In this post, I will explain how Keyak works by explaining how one can build upon the sponge primitive. Then I will share how my research group is planning to optimize it for performance.

So what is an authenticated cipher again?

Not surprisingly, it’s a crypto algorithm that will provide confidentiality and authentication to communicating parties. AES (the current encryption standard) only provides confidentiality; it protects from eavesdropping but provides no mechanism to ensure you are communicating with a friend or potential foe.

Why not just keep using HMAC’s?

An HMAC (hash-based message authentication code) will provide authentication but relies on hash algorithms separate from the cipher being used. Many different ciphers and hashes can be combined to provide authenticated ciphers, each with different trade-offs.

However, using two algorithms combined is relatively inefficient. Also because of the lack for a standard, unnecessary complications may arise. TLS, for example, has had a fair share of attacks, many of which can be attributed to the complicated nature and diverse cipher support of TLS.

And when security relies on a complicated protocol, it becomes difficult to program. Remember Heartbleed? Goto fail? BERserk?

How Keccak comes into play

To start, let’s make our own cipher that is based on Keccak and develop it until it is like Keyak.

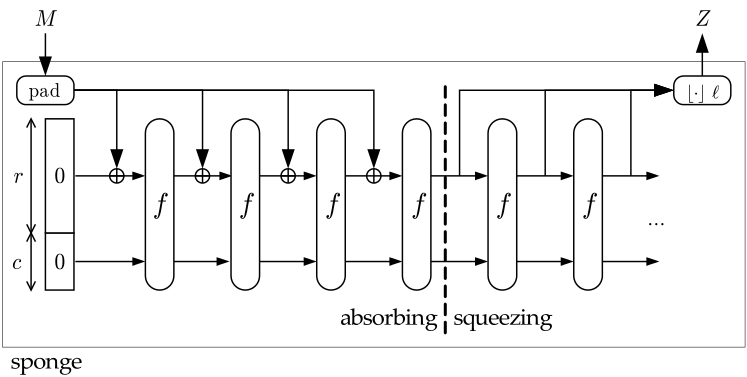

The Keccak sponge construction is illustrated below. All you need to understand is that it

absorbs up to 1600 bits at a time and outputs a 1600 bit permutation. Any additional input

can be XOR’d into the output block of a permutation round ƒ and applied to another ƒ. Rinse and repeat.

Above, the permutation ƒ is repeated 4 times in the “absorbing” stage for the input and 2 times in the “squeezing” stage

for the output. I.e. a 6400 bit message M is input and a 4800 bit hash Z is output.

Keccak specifically parameterizes how many rounds it should go through in each ƒ and then how much

output should be pulled at the end for the final hash. But for our purposes, it isn’t necessary

to think about parameters. Let’s implement our cipher.

Instead of feeding input to ƒ, we can first input a secret key

(and nonce). I.e. we

initialize the sponge state with our secret key. This will ensure all of our following applications of ƒ

are unique and full of entropy.

Now think that for each ƒ of the sponge we apply, we will get a new “hashed” version of our secret key in a way.

We get 1600 bits of new “hash” each time and we can do this as much as we want. It is these “hash-like” blocks

that we can XOR our message with. It’s like a pseudo one time pad.

Our recipient, who has the same secret key (and nonce), can compute the same “hash-like” blocks. Upon receiving the ciphertext, he can XOR it with his computed “hash-like” blocks to get the clear text message.

Pretty nice, huh? The security of the cipher is based on the security of Keccak, which we can take some comfort in.

Adding simple and strong authentication

We’re still missing the big picture: authentication. Our cipher currently only yields confidentiality. Let’s add a couple more steps.

So instead of just reapplying ƒ to the secret key to get a bunch of “hash-like” blocks,

we will include the message XOR’d in each input before reapplying ƒ to get the next block.

That way each new block is based on the initial secret key and the message being enciphered. After the whole

message has been encrypted, we can run f one more time to get a block that we will simply

use as our authentication tag.

Since this authentication tag relies on the sponge state that is a byproduct of the secret key and the enciphered message, only recipients with the exact secret key and unaltered ciphertext can recompute it.

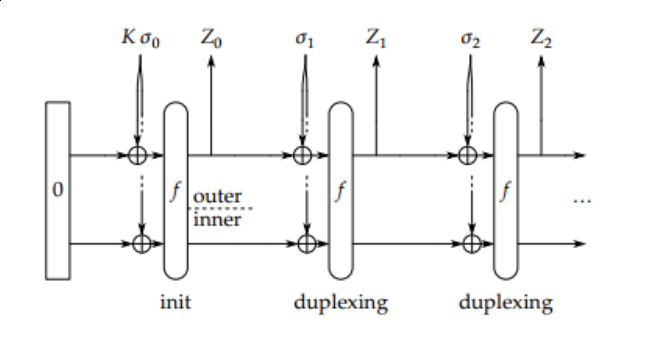

In the figure, K is our secret key and α0 is the nonce and padding. Let’s say that M is our clear text message.

For each block of M, the sender will XOR it with a “hash-like” block Z to make a block of cipher text, α. As long as there are blocks of

M left, the most recent α will be input to ƒ to create a new Z. After all message blocks are enciphered, the last α will

be input to ƒ again to create the authentication tag.

The receiver pretty much does the same thing except starts with the blocks of ciphertext (α) first rather then the plaintext. The message is revealed by simply calculating Z XOR α one block at a time.

Now for the exciting part.

The receiver can then apply ƒ one more time after decryption to recompute the authentication tag.

If it’s equal to the received authentication tag, then the message is authentic!

This is the basis for Keyak. I find it to be quite clever and superior to current authenticated crypto systems. Not only is it based on Keccak, but it combines encryption and authentication into one innate process. This sure beats the canonical method of encrypting and then calculating an HMAC over it.

Get prepared for creativity

There is certainly more to Keyak then the simple process I described. It supports meta-data

which can be sent as cleartext but will be included in ƒ’s input so that it is

still authenticated. It can be parameterized to set the block size, Keccak permutation used,

and number of encryption processes to run in parallel. Yup, Keyak supports parallelism as well.

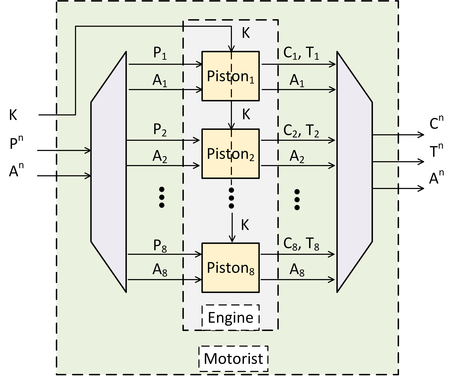

My impression is that Keyak is modeled after a motor boat. It has the following layers:

-

Motorist layer: responsible for handling the parameters. The motorist starts an “engine” which can be fed input (either ciphertext or plaintext) to be wrapped, where wrapping can be encrypting or decrypting. If decrypting, an authentication tag will also be input and verified. Only if the verification is successful, the engine will return the plaintext. If encrypting, ciphertext with a corresponding authentication tag will be output.

-

Engine layer: responsible for distributing blocks of input to it’s various pistons and piecing together the piston output.

-

Piston Layer: where the work actually gets done. Each piston can be initialized with a secret key and nonce. Each piston applies

ƒto a particular input to update the sponge state with a new “hash-like” block (Z). They do the wrapping of the input with the “hash-like” blocks to get the ciphertext or plaintext as in our simple algorithm above.

The pistons do the bulk of the work and each one is independent of the other. This allows them to be run in parallel for performance.

Optimizing Keyak for performance

For a naïve optimization, Keyak could be parallelized using thread level parallelism by simply assigning a thread for each piston. It’s a little overkill since each thread would be reduntantly executing the same instructions, just on different data.

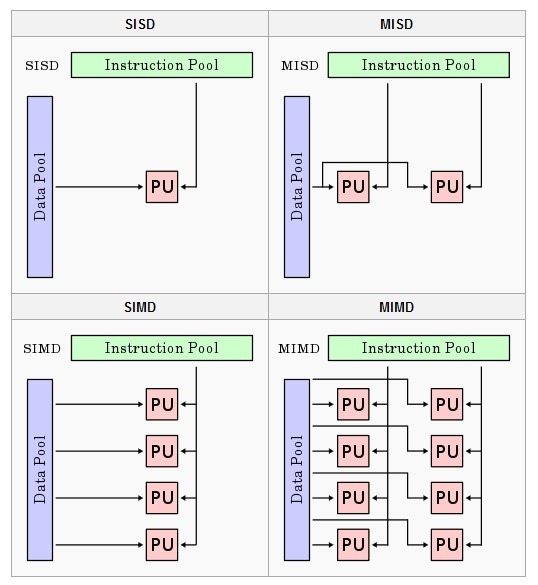

Let’s consider Flynn’s Taxonomy which contains 4 classifications for computer architectures.

-

SISD (single instruction single data) where 1 instruction is computed at a time, each on different data. Your regular CPU cores each do this.

-

MISD has multiple instructions executing in parallel for the same piece of data. This is not common but could be useful for fault tolerance.

-

SIMD has one instruction execute for multiple pieces of data. This is common in graphics processing and is abundant in GPUs.

-

MIMD is multiple instructions executing in parallel for different pieces of data. Modern CPUs do this by having multiple cores.

So pistons in Keyak are each running the same instructions, but each on different data. Any idea which architecture would be most efficient for optimizing Keyak?

If you think it’s SIMD (single instruction multiple data), then you are right!

My research group will be looking into using SIMD to optimize Keyak. Since SIMD is commonplace in graphics we will be implementating Keyak optimizations on a GPU.

Wrapping it up (pun intended)

Keyak is a great study. Not only is it a good read for it’s overarching Engine metaphor, but it’s a completely different way to do encryption from an algorithmic standpoint. It’s totally different from the typical substitution-permutation networks that many current ciphers are based on, including AES. It’s kind of weird, really; but that’s likely a good thing for a contender in the CAESAR competition.

This is a high level post; to learn more check out the Keyak website and the paper below.

References

-

Wetzels J., Bokslag W., “Sponges and Engines An Introduction to Keccak and Keyak”, 2016

-

Thanks to Bilgiday Yuce for the Motorist figure.